Storybeats

Storybeats differ from Storypoints in that they represent the temporal aspects of a narrative that carry the Audience from the beginning to the end of the story.

Each Throughline maintains a collection of Storybeats unique to that perspective. When illustrating your Storybeats don't worry about how they connect with Storybeats in other Throughlines: save that for the StoryWeaving stage of development.

Storybeats and Scenes

When it comes to the meaning, or message of a story, scenes don’t matter. A scene can start and stop any time, and can consist of any number of thematic issues. End the scene earlier or move its issues from one scene to the next, and the message stays the same. The subtext of the narrative remains intact.

And that’s all we’re really concerned about when developing a story in the Dramatica platform.

When it comes to meaning, scenes are arbitrary dividing lines. One man’s scene is another woman’s sequence—the markers are entirely subjective and therefore don’t factor into the message.

The Dramatica platform honors this reality of story by referring to individual events as Storybeats, not scenes. A single scene can contain any number of Storybeats. It can consist of one or 600–the final tally is entirely up to the writer.

What isn’t up to the writer is the importance of that beat to the overall message of the story. Storybeats communicate the meaning of your story.

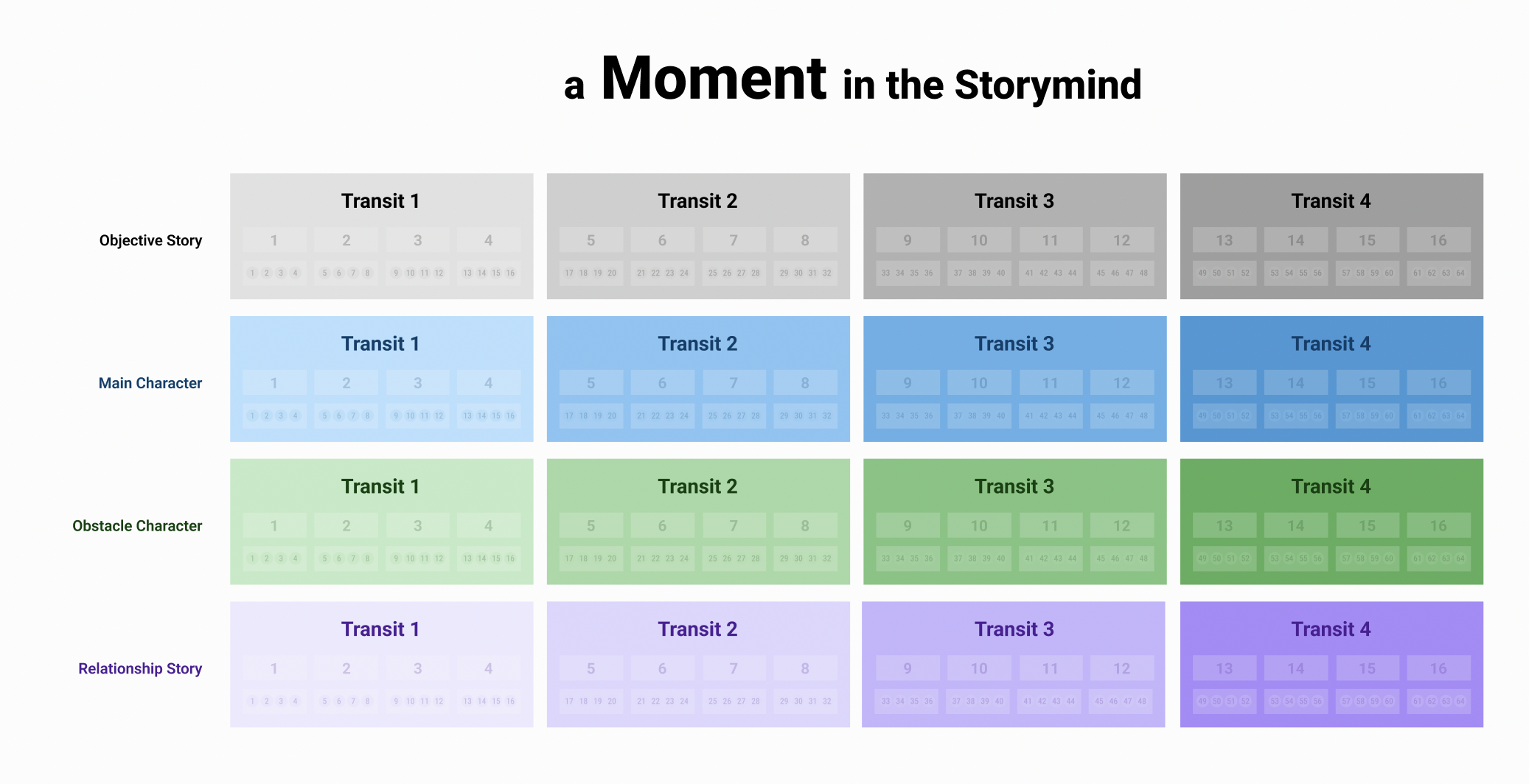

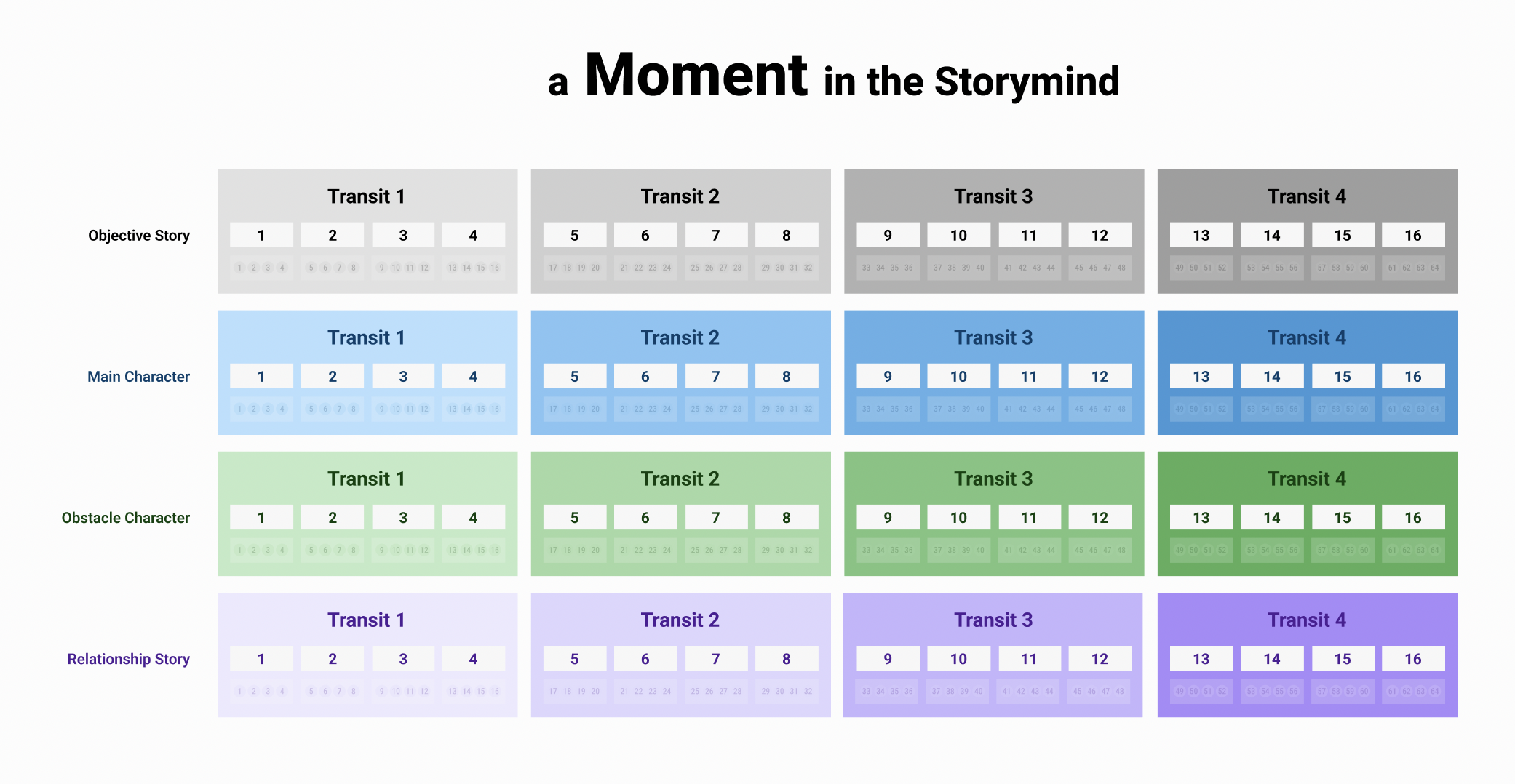

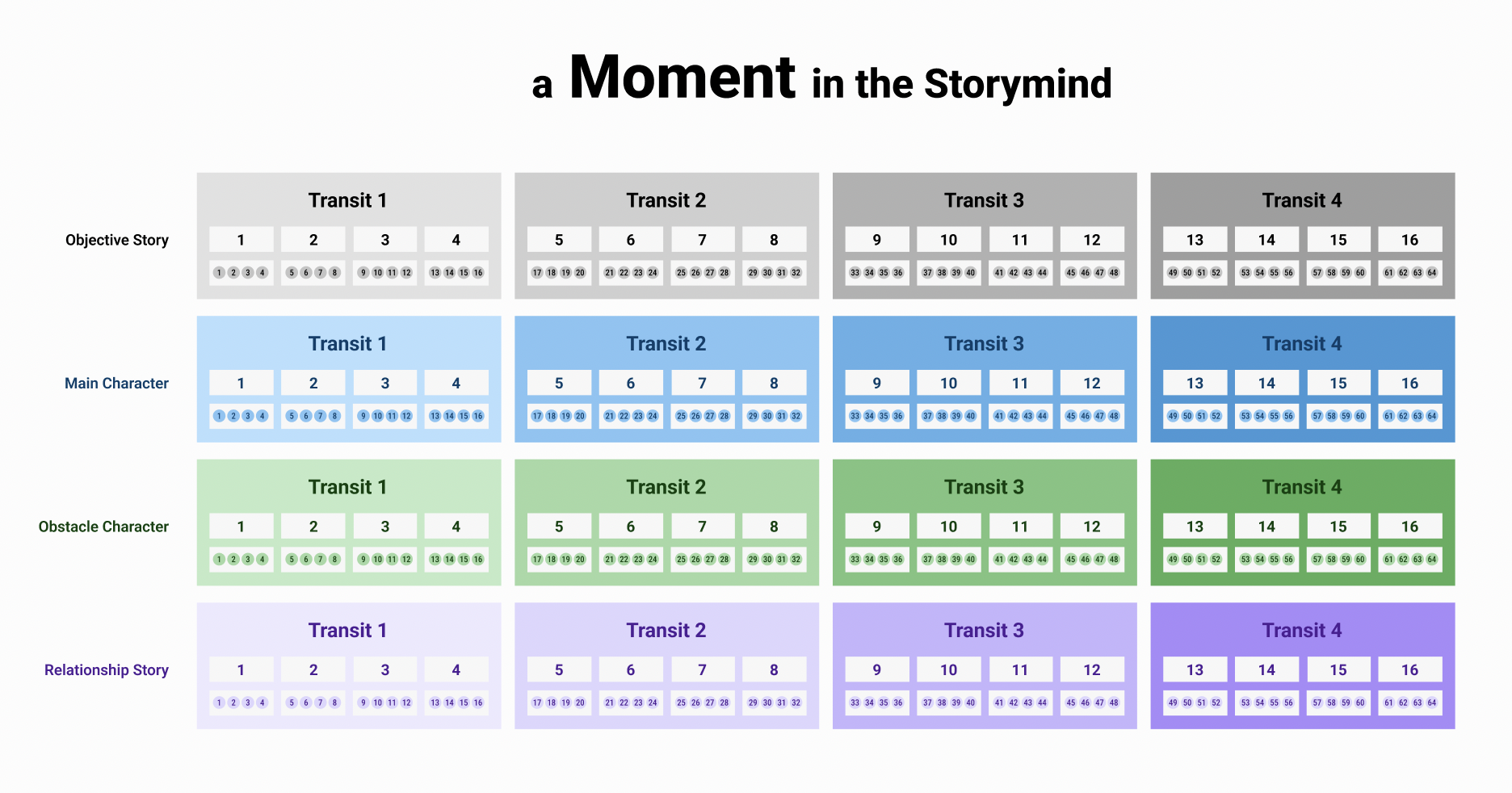

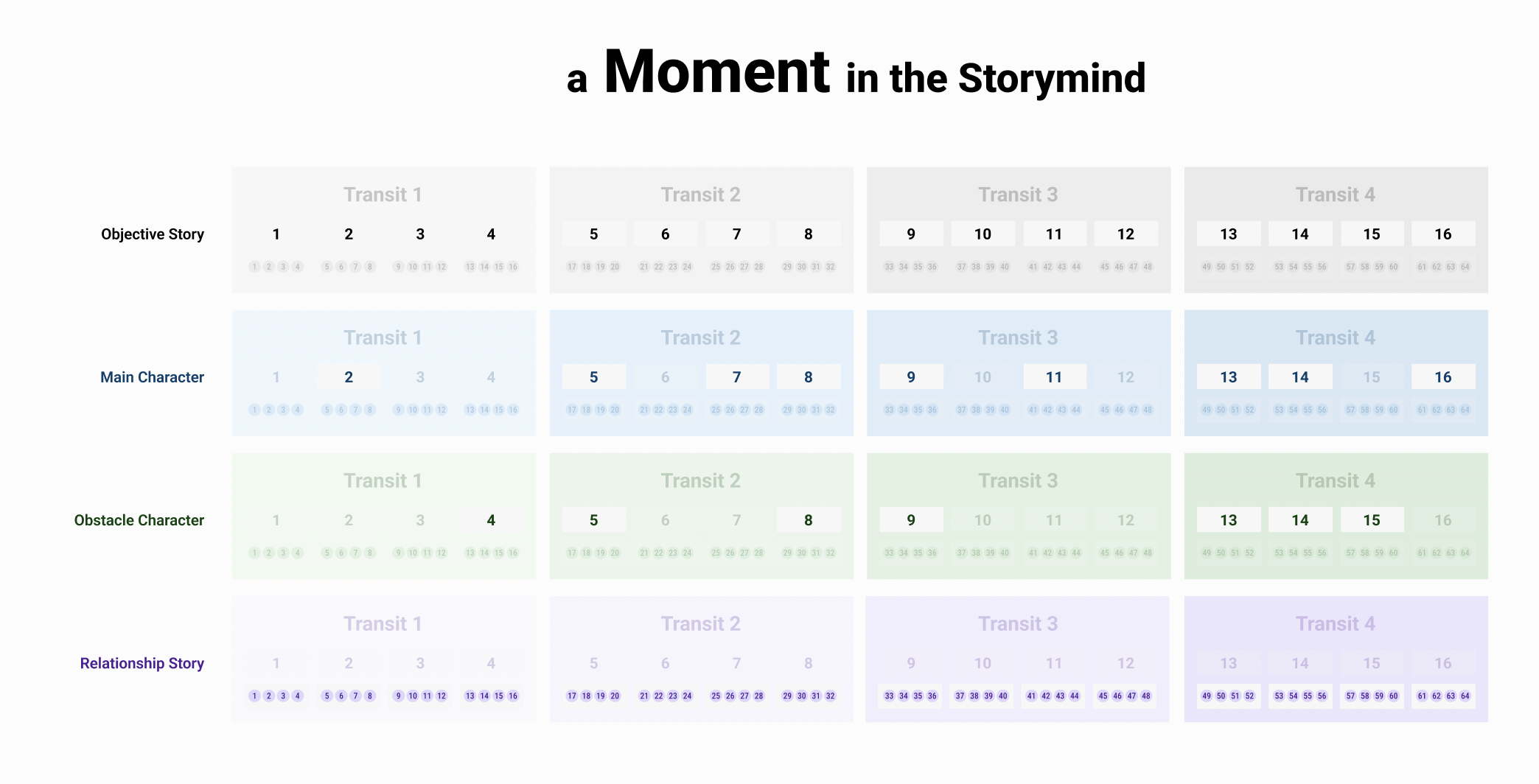

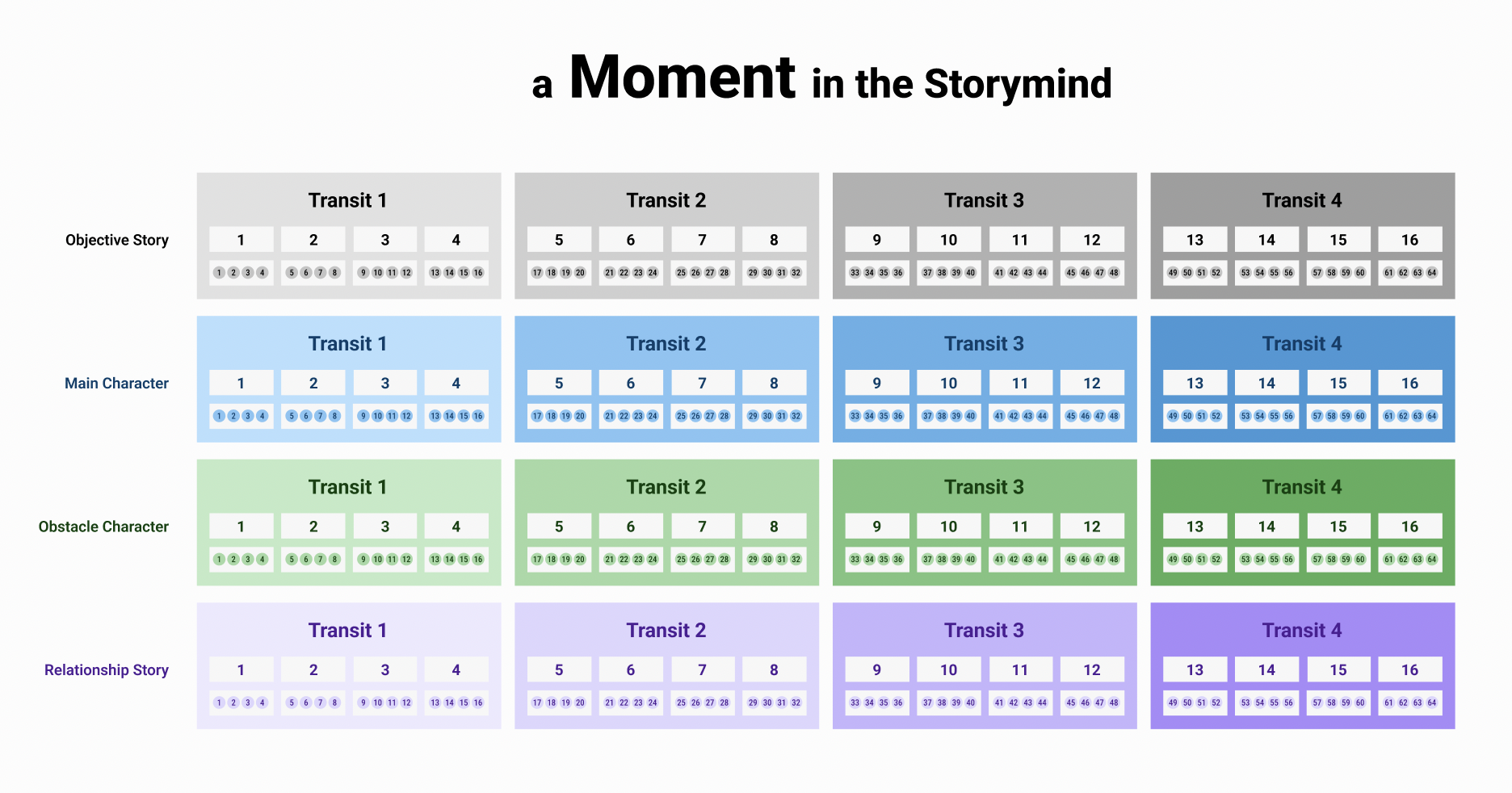

Single Story Moment Spanning Across Progressions

A Story Moment is a storytelling container, not a rigid structural boundary. In practice, one scene or sequence often carries multiple Events, and it can cross from the tail end of one Progression into the start of the next. This is why structure stays meaningful while pacing stays flexible: you can cut, combine, or extend scenes for rhythm without losing the Storyform’s thematic integrity.

Progression 1

Progression 2

Spans Event 1.2 → Event 1.4 and continues into Event 2.1.

Writing use: A single Story Moment can include the last three Events of one Progression and the first Event of the next.

TIP

The more Storybeats within a scene, the greater the dramatic impact and importance within the scope of the narrative. Think of the final Trench Scene in the original Star Wars: Objective Story Throughline Beats mix with Main Character that mix with Influence Character and Relationship Story Throughline Beats.

The reason why the climax of a story feels so monumental is not just because it's at the end of the story, it's because it's chock-full of important and meaningful Storybeats.

Storybeats: The Heartbeat of Your Narrative

Once we understand that Storybeats are the true building blocks of meaning in a narrative, it’s important to explore how these beats unfold. Unlike scenes, which can shift or blur in service to pacing or setting, Storybeats follow a consistent, thematic progression that drives the message of the story forward. This progression consists of patterns of conflict, transformation, and, crucially, reversal—where the energy of a narrative shifts direction through a dynamic relationship between key elements.

Storybeats are not just isolated events but moments of conflict where a character or story transforms. Each beat represents a thematic turn, where characters move from one perspective to another as a result of the conflict. This transformation is most clearly seen through the concept of reversal, where the initial thematic charge is dynamically reversed through the final beat in a sequence. Understanding how these beats reverse and transform provides the key to building a meaningful, resonant narrative.

The Nature of Storybeat Quads

At any level of storytelling—whether you’re focusing on a broad Signpost, a Progression, or a specific Event—the underlying structure is always based on a quad of thematic elements. These quads represent a complete cycle of conflict, action, justification, and transformation. What’s particularly unique about these quads is how the relationship between their elements always involves a dynamic reversal, regardless of which level you are analyzing.

In a Storybeat quad, the conflict begins with a charge coming in—the first thematic element that initiates the progression. As the story unfolds, it moves through subsequent beats, exploring how characters put things into practice and push for more in response to the initial conflict. Finally, the quad concludes with a charge coming out, where the energy is reversed, creating a new Contemplation or understanding.

This reversal occurs because of the diagonal, dynamic relationship between the first and last items in the quad. The first element sets the stage for the conflict, while the last element directly opposes or transforms that initial charge. Whether you’re looking at the grand arc of a Signpost, a smaller progression of events, or even a single beat, the same dynamic holds true: the narrative moves from one thematic pole to its counterpart, creating a meaningful transformation.

For example, if you start a quad with Self-Interest, you might exit through its opposite, Selflessness. Or if your conflict begins with Wisdom, it may eventually reverse into Enlightenment. This dynamic relationship between the initial and final elements in the quad is what gives Storybeats their thematic depth and complexity.

The Dramatic Scenarios Behind a Quad of Storybeats

Before diving into how Storybeat quads work, it helps to understand the Dramatic Scenario behind each beat. Every Storybeat is more than a label or plot moment—it is a compact dramatic unit composed of three interlocking parts:

- an Area of Exploration (Narrative Function),

- a Dramatic Function (Circuit), and

- an Area of Engagement (how it shows up in the story).

Taken together, these three parts form a single Dramatic Scenario that tracks how a mind encounters and works through inequity across a quad of Storybeats.

Within that quad, the four Storybeats typically distribute across four Areas of Engagement:

- Situations — States or conditions

- Activities — Actions or processes

- Aspirations — Goals or motivations

- Contemplations — Thoughts or reflections

These are the lenses through which the audience experiences conflict. Situations and Activities tend to feel immediately concrete and external—where things are, what people are doing. Aspirations and Contemplations round out the internal side—what characters want more of and how they make sense of what has happened.

Across a Storybeat quad, the Dramatic Scenarios built from these pieces move the story from conflict to transformation: circumstances generate pressure, characters act, desire intensifies, and reflection reframes meaning to prepare the next sequence.

From Structure to a Playable Storybeat

When a Storybeat feels abstract, this is the bridge back to writing. The Area of Exploration tells you what the beat is fundamentally about, the Dramatic Function tells you how it behaves in the circuit, and the Area of Engagement tells you how an audience experiences it. Combined, those three inputs produce a Dramatic Scenario you can actually stage, draft, and revise at scene level.

flowchart LR AE["Area of Exploration<br/>(what this beat is about)"] DF["Dramatic Function<br/>(how this beat behaves in the circuit)"] AG["Area of Engagement<br/>(how the audience encounters it)"] AE --> DS["Dramatic Scenario<br/>(single complete beat statement)"] DF --> DS AG --> DS DS --> PSI["Playable Storybeat Illustration<br/>(what you can write, stage, or film)"]

Writing use: If a beat feels vague, diagnose which input is missing: what it explores, how it functions, or how it engages the audience.

Dramatic Scenario

The three parts of a Dramatic Scenario—Area of Exploration, Dramatic Function, and Area of Engagement—should be read as a single statement so the intent of the beat stays clear.

For example:

“What has already happened creates tension in states or conditions.”

- Past / Potential / Situations

Flipped: “States or conditions create tension regarding what has already happened.”

- Situations / Potential / Past

In both cases, you can feel the whole Dramatic Scenario at once:

[Area of Exploration] + [Dramatic Function] + [Area of Engagement]

This is how you keep each Storybeat tightly aligned with the Storyform while still thinking in terms that are playable, filmable, and writable.

TIP

The Narrative Argument (Storyform) sets the progression of a mind as it encounters inequity (through Signposts, Progressions, and Events). Each Dramatic Scenario anchors that abstract argument in a specific beat so the throughline stays thematically precise.

Components of a Dramatic Scenario

Every Dramatic Scenario is composed of three parts:

- Area of Exploration: the narrative “aboutness” of the beat (the Narrative Function).

- Dramatic Function (Circuit): how the beat relates to its siblings in context of the larger circuit.

- Area of Engagement: the conceptual mode by which the beat is experienced in the story.

Area of Exploration

The Area of Exploration is the first and most important part of any Dramatic Scenario. Tied to a specific scope and location within the Storymind model (e.g., Past, Memories, Understanding, Obtaining, etc.), it identifies the key thematic element the beat must explore.

This is the structural “what” of the Storybeat—the core piece of Theme being examined.

If all else fails, as long as the Author finds a way to bring this element of Theme into the Illustration, the Storybeat will resonate with the rest of the narrative. The Area of Exploration keeps the beat plugged into the Storyform’s argument, even as the surface storytelling shifts.

Dramatic Function (Circuit)

Rarely does a Storybeat resonate in isolation. The Dramatic Function describes how the beat operates within a circuit of sibling beats, using the analogy of an electric circuit:

Charge In to Charge Out (Storybeat Circuit)

Think of a Storybeat quad as a dramatic version of an electrical circuit. You introduce narrative Potential (stored tension), push it through Resistance (friction and pushback), move it with Current (conflict in motion), and land in Power (impact, payoff, or reframe). This keeps a beat from feeling static: it carries charge from entry to exit, so the audience feels movement in meaning rather than just more plot information.

Potential

Middle Processing

Resistance

Current

Power

Dynamic polarity / reversal runs from Beat 1 to Beat 4.

Writing use: Enter with a clear tension, let the middle beats push and pull (including bounce-back between Beats 2 and 3), then land on a meaningful reframe.

- Potential — Tension

- Resistance — Pushback

- Current — Conflict in motion

- Power — Impact or payoff

A Storybeat marked as Potential sets up tension around its Area of Exploration; Resistance pushes back against that tension; Current drives conflict through active friction; Power delivers the impact that transforms understanding or stakes.

Across a quad of Storybeats, these functions distribute so that no beat stands alone: each one either loads, pushes, channels, or discharges the inequity under examination. The Dramatic Function tells you how this beat is doing its job in relation to the others.

Area of Engagement

Previously treated as the “abstraction of the Storybeat,” the Area of Engagement describes how the audience encounters the beat—the conceptual mode through which the Storybeat is illustrated.

The four Areas of Engagement are:

- Situations — States or conditions

- Activities — Actions or processes

- Aspirations — Goals or motivations

- Contemplations — Thoughts or reflections

The first two are external in nature; the latter two are internal.

In practice:

- Situations establish the conditions that generate initial tension (“being trapped in a failing town,” “a marriage under quiet strain”).

- Activities capture what characters do in response (“investigating a disappearance,” “training for a risky heist”).

- Aspirations give voice to the forward-leaning “more” the characters reach for—desire, ambition, pressure, yearning (“wanting out,” “pushing for recognition,” “refusing to let go”).

- Contemplations consolidate or reframe meaning—how characters think about what has happened, revisit assumptions, or shift perspective (“reconsidering who’s to blame,” “questioning their own role in the mess”).

Aspirations and Contemplations will often appear intertwined on the page, but they serve distinct roles in the Dramatic Scenario:

- Aspirations drive the story forward.

- Contemplations reset or reframe the story’s understanding.

Dramatic Scenarios Across a Storybeat Quad

Within a quad of Storybeats, each beat has its own Dramatic Scenario—its own combination of Area of Exploration, Dramatic Function, and Area of Engagement. Taken as a set, the four scenarios map a complete mini-cycle of conflict and change.

You might see something like:

Area of Exploration: Past

- Function: Potential

- Engagement: Situations

- Scenario: “What has already happened creates tension in states or conditions.”

Area of Exploration: Past

- Function: Resistance

- Engagement: Activities

- Scenario: “Attempts to work around what has already happened meet pushback in what people do.”

Area of Exploration: Past

- Function: Current

- Engagement: Aspirations

- Scenario: “Desire to escape what has already happened drives escalating conflict in what characters want.”

Area of Exploration: Past

- Function: Power

- Engagement: Contemplations

- Scenario: “Reckoning with what has already happened lands with impact in how characters think about it.”

Across this quad:

- The Area of Exploration (Past) keeps the Theme coherent.

- The Dramatic Functions (Potential, Resistance, Current, Power) move the conflict through a circuit.

- The Areas of Engagement (Situations, Activities, Aspirations, Contemplations) shift the way the audience experiences that conflict—from external conditions to internal reflection.

The final beat’s Contemplations often provide the reframing that resets the cycle, setting up the next quad of Storybeats to explore a new Area of Exploration or a new level of the same one.

When you think of Storybeat quads in terms of these Dramatic Scenarios, you gain a precise yet flexible way to design sequences: each beat has a clear function, a clear thematic target, and a clear experiential mode—without ever losing sight of the Storyform’s overarching Narrative Argument.

A Sample Storybeat Quad

With the components of a Dramatic Scenario in mind, let’s look at how they play out in practice. Consider a Signpost of Being, where the Area of Exploration is fixed at Being, and a quad of Progression Storybeats walks that exploration through four different Areas of Engagement:

Permission (Being as a Situation) The conflict begins in a specific Situation: what is allowed and what is not? Here, the Dramatic Scenario might read as “Being, under the terms of Permission, generates tension in states or conditions.” This beat loads the circuit with its initial charge—establishing the limitations of what characters can and cannot “be,” and defining the conditions under which the rest of the quad must operate.

Need (Being as an Activity) The characters then respond by shifting into Activity. They put roles, expectations, and identities into practice—doing what is required, or what they believe is required, to maintain or challenge their Being. The Dramatic Scenario becomes “Being, framed as Need, expresses itself through what people do.” The story moves from merely having constraints to acting within or against them, pushing the circuit into motion.

Expediency (Being as an Aspiration) As the doing continues, pressure intensifies in the realm of Aspiration. Characters start reaching for shortcuts and quick wins—ways of “being” that promise relief without fully addressing the underlying inequity. Here the Dramatic Scenario might be “Being, filtered through Expediency, drives tension in what characters want and push for.” Desire, ambition, and urgency collide with the earlier conditions and actions, escalating the conflict in the forward-leaning “more” they reach for.

Deficiency (Being as a Contemplation) Finally, the quad culminates in Contemplation. The characters confront what is missing in who they are or how they have been. The Dramatic Scenario shifts to “Being, viewed through Deficiency, lands with impact in how characters think about what they lack.” This is the charge coming out of the circuit: a reframing or reversal of the initial Situation. If the quad opened with Permission locking things down (“You’re not allowed to be that”), it can close with Deficiency reinterpreted (“What’s really driving all this is what we aren’t yet—and now we see it”). That new understanding resets the terms of the conflict and prepares the next cycle of Storybeats.

Taken together, these four Dramatic Scenarios show how a single Area of Exploration (Being) can be driven through a complete circuit of tension, response, escalation, and reframe simply by shifting the Area of Engagement from Situations to Activities to Aspirations to Contemplations.

This pattern of progression and reversal is not unique to the Signpost level. Whether you are working at the scale of an overarching storyline or a single scene, the quad structure remains consistent: the first Storybeat sets the stage for the inequity, the middle beats work it through in action and pressure, and the final beat dynamically transforms or inverts that initial charge—providing thematic resolution for this cycle and setting up the next.

How Quads Create Thematic Reversals

The key to understanding Storybeat quads lies in their inherent balance between opposing forces. Each quad, whether at the Signpost, Progression, or Event level, contains a diagonal pairing between the first and last beats. This pairing creates a reversal, where the initial conflict is transformed through the final beat, leading to a new understanding or Opinion.

This dynamic relationship is what drives the transformation within a story. For example, in a quad involving Self-Interest, the characters may start out motivated by their own needs and desires. As the conflict escalates through actions and justifications, they begin to question the validity of these self-centered motivations. By the time the final beat arrives, the Opinion may shift entirely to Selflessness, where the characters realize the importance of others over themselves. The reversal from Self-Interest to Selflessness completes the thematic progression and sets the stage for further conflict.

In other cases, a quad might begin with Wisdom, where characters rely on experience and knowledge to navigate a challenge. But as the conflict unfolds and they justify their actions, the narrative energy shifts, culminating in Enlightenment—a deeper, more transformative understanding that transcends simple wisdom. This diagonal pairing between the beginning and ending beats creates a foundational thematic shift, which is the hallmark of a well-structured Storybeat quad.

The Pinball Machine of Storybeats

To visualize how these quads work in practice, imagine a pinball machine. The initial charge is like launching a silver ball into play, where it begins by entering a Situation—the thematic issue that sets up the conflict. From there, the ball bounces among Activities and Aspirations. Each time the ball strikes a bumper, it ricochets in a new direction, keeping the narrative energy in motion.

Eventually, the ball exits through a new Contemplation, where the conflict is reframed and transformed. This process is not linear but dynamic—the ball doesn’t simply follow a straight path; it zigzags through the different elements of the quad, creating tension and unpredictability. The ball’s final exit represents the charge coming out of the Storybeat, where the narrative energy is reversed and recharged, ready to begin a new sequence of beats.

The Universality of Reversals in Storybeat Quads

Whether you are working at the broad level of a Signpost, the more focused level of a Progression, or the granular level of a single Event, the quad structure remains the same. The narrative moves from an initial conflict (Situation) through Activities and Aspirations, ultimately resolving into a new Contemplation. This consistent structure allows for thematic coherence across all levels of storytelling, providing the foundation for both conflict and transformation.

In Dramatica, the key to building meaningful narratives lies in understanding how these quads work together to create reversals. The initial charge of a Storybeat doesn’t simply resolve itself; it transforms through dynamic relationships, ensuring that the narrative constantly evolves and deepens. The balance between opposing forces in each quad gives your story momentum and purpose, moving it toward greater conflict and eventual resolution.

The Crucial Scenes of a Narrative

Within a Storyform, a handful of quads deliberately break the usual Situation → Activities → Aspirations → Contemplations flow. These are “Crucial Scenes”—hinge beats where the charge of the story flips direction and meaning re-anchors. Instead of leading with a Situation that provokes Activities, you might begin with an Activity that instantly crystallizes into a Contemplation, which then destabilizes the Situation and compels fresh Aspirations. These inversions aren’t glitches; they’re a function of the Storyform’s Dynamics and Throughline arrangement, introduced to keep the narrative from settling into a predictable cadence and to catalyze genuine reappraisal.

For example, consider an OS Signpost about “Doing.” In the usual order, you’d establish the Situation (museum lockdown tightens), move into Activities (the crew initiates the heist), surface Aspirations (they push for a shortcut), and end in a new Contemplation (the team judges the leader reckless). In a Crucial Scene, the sequence might open with an Activity (the leader smashes the display early), jump to a Contemplation (the crew instantly judges him reckless), which shakes the Situation (security protocols escalate unexpectedly), forcing new Aspirations (they must push for a riskier exit). This reordering creates a sharper pivot: conflict erupts first and redefines context after, producing the felt “lurch” of a turning point rather than the smoother escalation of a standard beat.

Writing an Effective Storybeat

Too many writers fall into the trap of simply using the illustration of a Storybeat verbatim, without taking the time to consider WHY this particular illustration is problematic within the context of the story. We refer to this as "Mad-libbing" the Storyform, and is a particular problem with those leveraging AI with Dramatica theory.

Storybeats are an indication of the source of conflict in a narrative--take care to make sure you go above and beyond simply copying the term for your story.

In The Shawshank Redemption, the first Main Character Signpost of Red's Throughline is an Area of Exploration of Becoming with an Illustration of "falsely reforming" The Mad-libs style of illustrating this part of the Dramatica storyform would find many Authors writing this:

Red shows up to the parole board falsely reforming himself.

While this is OK, it's only illustrating 50% of what is actually needed to fully understand the conflict of this particular Storybeat.

It's not enough to simply copy and paste the Illustration, the Author's responsibility is to show HOW that is problematic for the characters in that scene. How does Stephen King show why Red "pretending something is OK" ends up being a problem for him?

Some people are perfectly fine with pretending everything is OK--as Authors, we can't assume that just because we think this illustration is a problem that means everyone else will think it is a problem as well.

We need to show the Narrative Function of conflict explored in the Storybeat to be problematic. This is where the Dramatic Function and the Areas of Engagement come in handy (in this example, the two are Current (Conflict) and Asprirations). We need to show how and why it creates conflict within the narrative.

So, how does Red find conflict in "falsely reforming"?

Main Character Signpost 1 of Becoming: Red shows up to the parole board already falsely reforming himself into the kind of “rehabilitated” inmate he believes they want to see: he talks about his aspirations to live an honest, productive life and insists he’s a changed man, but it’s all a crafted identity aimed at release rather than a genuine shift. This hollow self-transformation collides with the board’s sense that nothing real has changed, generating conflict as his stated aspirations ring false and his bid for freedom is denied. The same pattern of falsely reforming continues when he later presents himself to Andy as an adjusted, harmless old-timer and steels himself against the sounds of inmates being beaten at night, maintaining the façade of a reformed man instead of confronting what he would actually need to become to reach the future he claims to be aiming for.

Why is this important?

Well, now we have more meaningful Storybeats to refer to when we go to write our story. It's not just that Red is pretending, it's that his pretending is causing him great personal conflict. This connection between Storytelling and subtext (meaning/Storyform) clues the Audience in on what it is we are trying to say with our story. There is a greater purpose behind the scenes.

And it will help us generate even greater Storytelling further on down the line.

By illustrating this first Act of Red's as showing pretending as a problem, we prime the Audience with an understanding of the kind of resistance Red is creating for himself. We know where his self-sabotage is coming from, and we recognize it as an opportunity for growth.

Illustrating the Turning of a Storybeat

When it comes to illustrating a family of Storybeats (e.g., the Signposts of a Throughline, Progressions of a Signpost, or Events of a Progression), writers can benefit from taking an outside-in approach that honors the meaning of a Storybeat over the linear progression of beats that appear within.

The Dramatic Circuit Analogy

Think of each Signpost, Progression, or Event as a dramatic circuit, such that the energy of the narrative flows in through the first child Storybeat and then exits out that circuit through the last Storybeat. The middle two Storybeats simply process, or work through, the narrative energy as it transmutes from beginning to end.

You might have heard this referred to as "turning a scene" elsewhere, or you might know this as the concept of "negative" and "positive" scenes, such that one enters a scene with a positive charge, and then leaves with a negative charge (or vice versa).

The reason others have picked up on this in the past is that, for the most part, the first and last Storybeat of a Progression, Signpost, or Event are typically polar opposites of a Dynamic Pair. When viewed within the context of the Dramatica quad, energy arrives into the scene in the upper left quadrant, and then exits out through the bottom quadrant.

The Outside-In Approach

When illustrating a Signpost/Progression/Event, consider the first and last Storybeats first, and then proceed inward to address the other two. In this way, the writer ensures a consistency of thematic integrity towards the parent Storybeat.

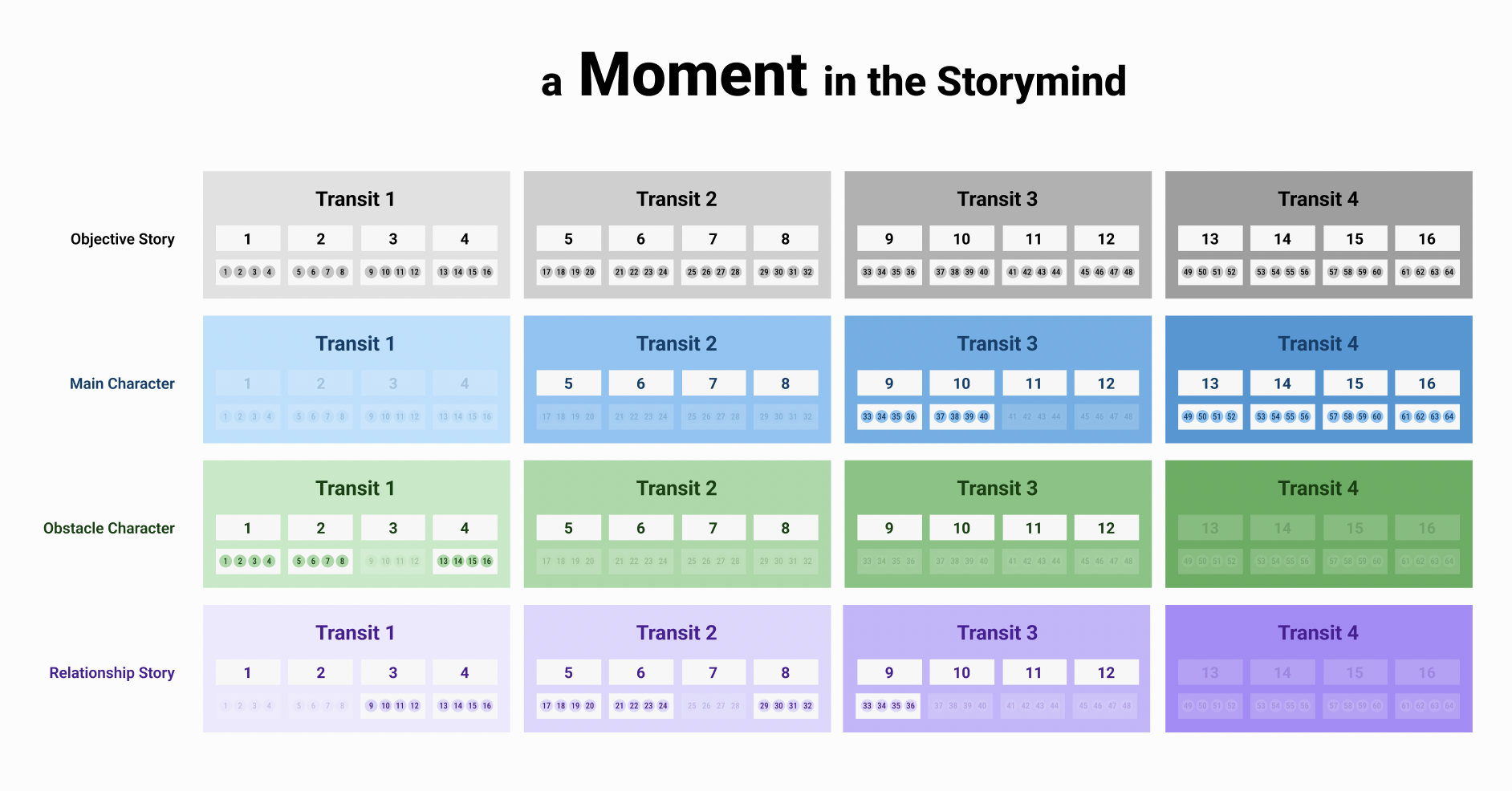

The Scope of a Storybeat

While presented with different labels, every Storybeat theoretically is the same exact thing: a single point in time along the thread of narrative that is your story. By offering you the chance to see these Beats at different resolutions, Authors can determine for themselves how much time to spend on a particular part of their story.

More detail = more time, and more specificity.

Fractal Storybeat Scale

Storybeats are fractal: the same structural logic appears at larger and smaller scales. You can zoom out to map a whole Throughline across acts, zoom in to design a single sequence, or go even tighter when outlining a specific scene run. For long-form work, this matters because an episode can function like a Storybeat in a season, while a season can function like a Storybeat in a multi-season arc. Writers can expand outward for macro coherence or narrow inward for moment-by-moment precision without breaking the underlying argument.

Writing use: Keep this map structural only: Signposts break into Progressions, and Progressions break into Events.

The Dramatica platform offers three sizes (or scopes) of Storybeats:

- Signposts

- Progressions

- Events

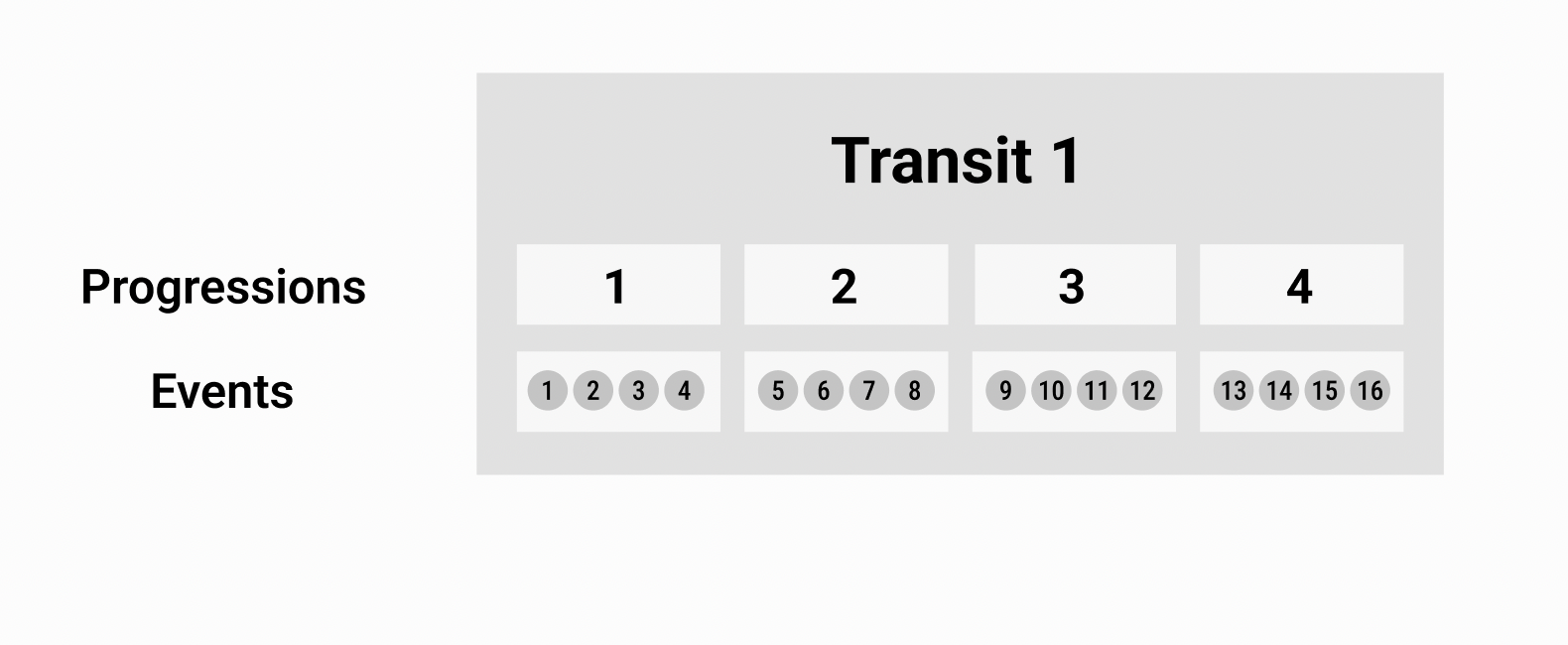

Signposts are the largest size of Storybeats, with Progressions being the next size down, and Events the smallest. There are four Signposts in every Throughline, four Progressions in every Signpost, and four Events in every Progression.

Signpost

Within the context of a complete story, you will find a total of 16 Signpost Storybeats--four for each of the Four Throughlines. They will feel like "Acts" because they span a greater amount of time within the narrative.

Progressions

Progression Storybeats are breakdowns of their parent Signpost-level Storybeat. Think of these Progression Storybeats as telling the mini-"story" of the Signpost Storybeat above them. If you break a Storybeat labelled "Progress" into the Progression Storybeats of "Truth, Evidence, Suspicion, and Falsehood," then those four Progression would tell the story of Progress for that Throughline.

In the beginning of a story, Progression Storybeats often end up in their own individual Scenes, cordoned off from the others. As the narrative progresses, and tension winds up, a "Scene" in your novel or screenplay might contain three or four of these Progressions (think the ending trench scene in the original Star Wars, where Storybeats from the Main Character, Influence Character, Relationship Story, and Objective Story fall into one action-packed moment).

Events

Events Storybeats illustrate the story of a Progression Storybeat. We refer to them as simply Events because they represent the smallest unit of narrative you can see without losing context of the entire story. If you were to dive further, you would be telling an entirely new story within the framework of your original story (Television series and seasons and individual episodes work this way).

Think of the Events as a specific outline for what happens in your Progression Storybeat from beginning to end. Again, in the beginning these four Events will represent the beginning, middle, and end of individual Progressions. As you get closer to the end, several groups of Events will work together to tell a highly dramatic and consequential climactic moment.

Managing Different Sizes of Storybeats

Storybeats are essentially the fundamental units of storytelling. Signposts, Progressions, and Events are all forms of Storybeats, each varying in size and complexity.

Signposts can be considered as the overarching narrative flow, representing larger changes or shifts in the story. Progressions are smaller steps that contribute to these major transitions, while Events are the smallest units, depicting individual incidents or occurrences.

The manner in which you structure these Storybeats largely depends on your creative vision as the Author. You can choose to begin with the Signpost, followed by the Progressions, or you can integrate the Signpost within the Progressions. Both approaches are "correct" in the sense that they're both viable Narrative Functions for structuring your narrative.

However, it's crucial to maintain balance and avoid excessive repetition. Too many Signposts of the same type within a single Act can make the narrative feel stagnant and tedious.

And, yes, the storytelling of the Signpost can encompass that of the Progressions. There's a lot of flexibility here to experiment with different approaches and see what best fits your story.

In terms of interacting with the Dramatica platform, it shouldn't be an issue regardless of the approach you take. The application should be able to understand and adapt to the narrative structure you've chosen, as long as it's coherent and consistent.

There's no rigid rule that dictates how to weave Signposts, Progressions, and Events together in your story. Your priority should be to deliver a compelling and engaging narrative that effectively communicates your story's message to your Audience.

Setting the Level of Detail

NOTE

The following section covers how to adjust scope within the Subtxt application. We are currently in the process of merging Subtxt into the Dramatica Narrative Platform. While the following applies to its usage within Subtxt, you may find it beneficial to continue reading in order to gain a better mental model of how Storybeats work within a Storyform.

When you begin developing your story with the Dramatica platform, the number of Storybeats is quite manageable. Four Signposts in Four Throughlines gives you the minimal coverage for a complete story, and that relatively small amount of information (16 Storybeats) is easy to navigate during development.

As you grow that number beyond the initial sixteen Storybeats, some Throughlines can become quite overwhelming to navigate. As you zoom in and out mentally from the Signpost level down to the Event level, you find yourself lost and wishing there was a way to focus in on one level at a time.

There is.

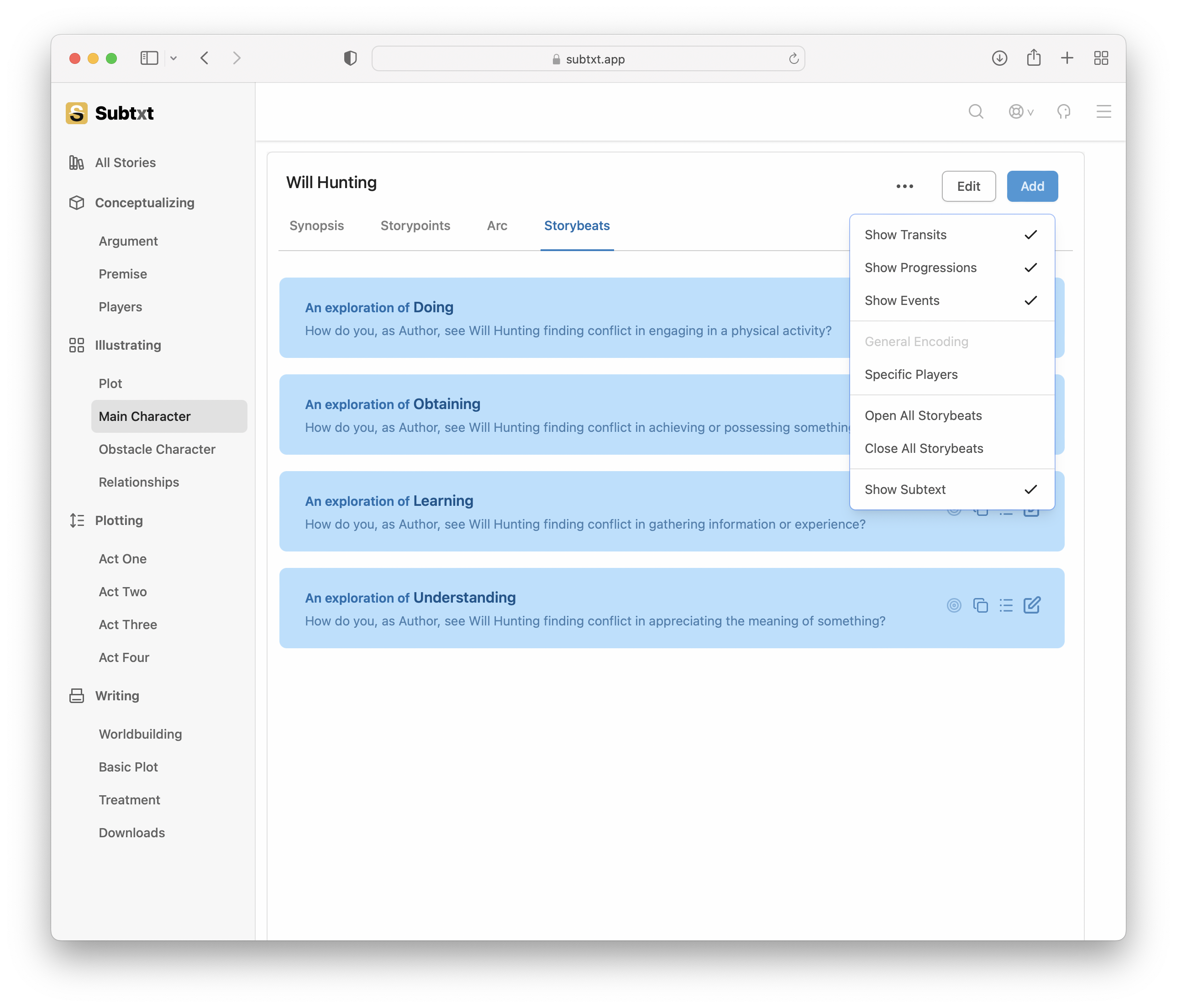

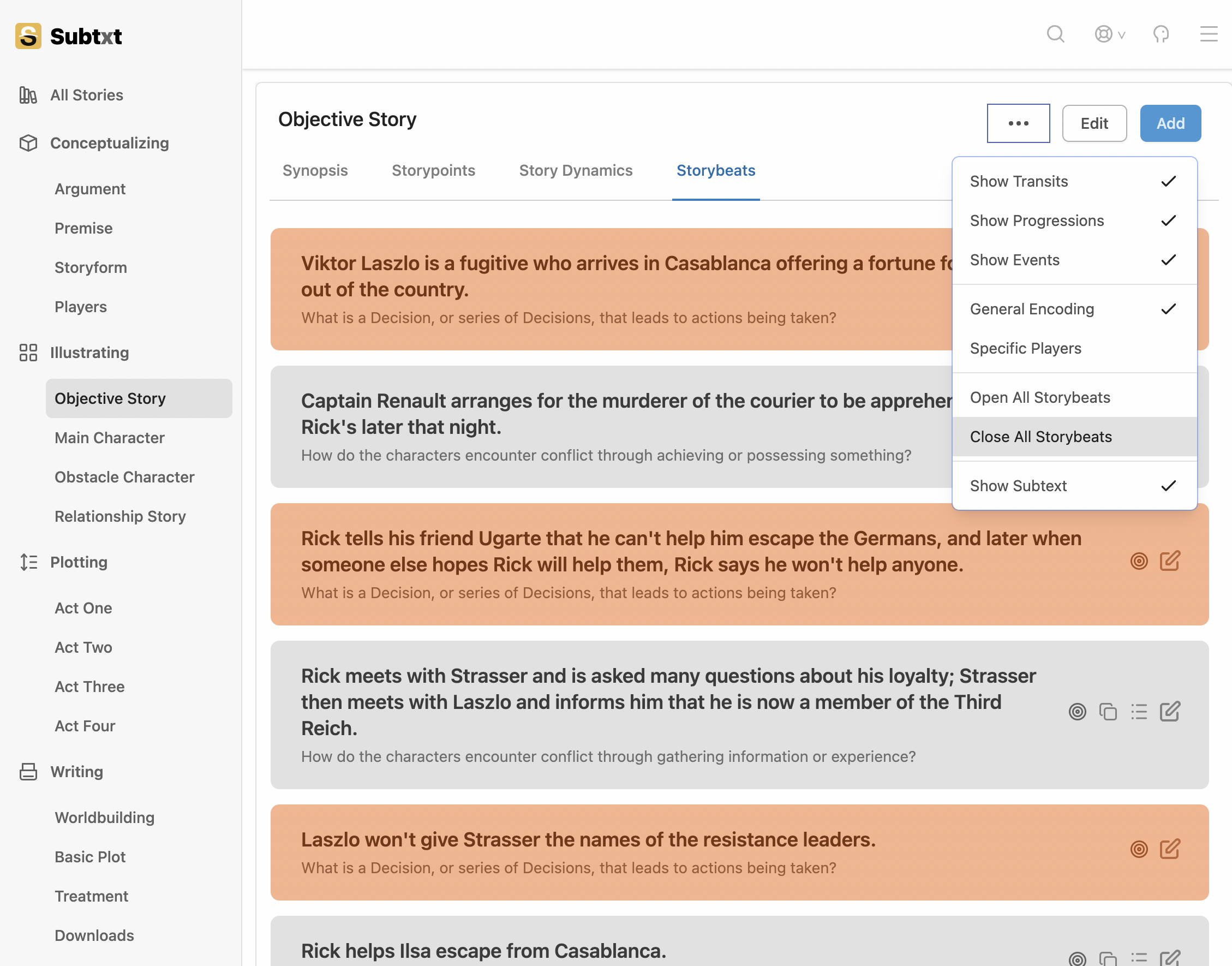

At the top of each Throughline, you'll find a three "dots" icon that you can click in order to set the level of detail.

The choices within this dropdown menu are multi-selectable, meaning you can show just the Signposts, or just the Signposts and the Progressions, or just the Events. Any combination of all three will adjust the current Throughline View to a scope that is more manageable for you and your writing process.

The Storybeats of a Complete Story

At the minimum, a story needs the 16 Signposts to be considered a complete story. These initial 16 StoryBeats are essential for communicating the essence of your Narrative Argument. Leave one or two of these Storybeats out, and you risk losing your Audience. Repeat the same item over and over again, and you risk beating your Audience over the head with your message.

It's a tender balancing act, and one that you'll come to know intuitively the more you work with the Dramatica platform.

Note that you do not have to illustrate every single Signpost, every single Progression, and every single Event. Stories are a mix of larger-sized Storybeats interspersed with smaller-sized Storybeats. As long as the Audience has enough information to connect the dots between these Dramatic Scenarios, the meaning of the story will hold together and the end result will be that of a complete story.

Breaking Down Storybeats

One of the more powerful features of the Dramatica platform is the ability to breakdown Storybeats into their smaller units of dramatic progression. Signposts break down into Progressions, while Progressions break down into Events.

TIP

You can directly ask Narrova to provide you with these breakdowns: e.g., "Please breakdown Signposts 1-4 for the Relationship Story Throughline" or "Can I see the Events for the second Progression of Signpost 2 of the Objective Story Throughline?"

You will find the Breakdown button for each Storybeat at the base of the Storybeat window. Select the Breakdown (either Progressions or Events) and then choose whether you want the platform to generate Storytelling within each Beat OR if you would rather it just provide the Beats without Storytelling. Selecting the former will set the appropriate Narrative Task and then return you to the Building screen as the AI illustrates this part of your story.

When the Task is complete, you will find the Storybeats beneath and within their parent Storybeat. You are always free to then go in and adjust the Storytelling, and even create different versions of each Storybeat to suit your imagination.

NOTE

The term "Breakdown" comes from our experience working in the animation industry. Supervising animators would first draw "key poses"--those poses key to communicating a certain bit of acting--and then hand off the scene to an assistant animator to "breakdown" the poses. These in-between poses would help bring the scene to life by giving the key poses fluidity and flow. Same thing with the Breakdown Storybeats in the Dramatica platform.

Think of Storybeat Breakdowns as the progression of the story within a specific Storybeat. If a particular Storybeat tells you that your characters are learning something (a Signpost of Learning), then how they go about learning is covered step-by-step by the Storybeat Breakdowns (in this case, a set of four Progressions).

It's up to you, the writer, to determine how much you want to go into detail for your story.

The Tendencies of the Medium

If you're writing a screenplay, you likely won't need to breakdown the Signposts for the Influence Character or the Relationship Story Throughlines. In fact, we strongly suggest you don't.

On the other hand, if you're writing a novel, or longform television series, breaking down Signposts and Progressions will give you the material and inspiration you need to fill in your story's larger storytelling real estate.

If you're writing a short story, we absolutely recommend you don't breakdown any of the Signposts. In fact, you're probably best served turning off some Throughlines. You can learn more in our section on Writing Short Stories.

Deleting a Breakdown Storybeat

Occasionally, you may find that the Breakdown Storybeats are too detailed for your story. You may only want one or two of these breakdowns. This is a perfectly legit approach and won't disrupt the integrity of your narrative.

TIP

Think of your narrative as a range of mountain peaks. Sure, you can zoom in and see the trees and the rocks and maybe a bear or two, but if you leave out a bear or even a couple trees, you'll still see a mountain. Same thing with your story--the initial 'big' Storybeats are far more important than the smaller Breakdown Beats when communicating your story's Narrative Argument.

You delete a smaller Storybeat the same way you delete the larger ones. Select "Edit" at the top of the Storybeat tab and then tap the red "minus" icon to the left of the Storybeat.

If a larger parent Storybeat contains smaller children Storybeats, the Dramatica platform will ask you ahead of time if you want to erase those Storybeats as well. Note that once you delete a Storybeat, any and all storytelling attached to it will be lost.

Story Drivers and Storybeats

In the Objective Story Throughline, you will find "orange"-colored Storybeats interspersed throughout the plot of your story. These "beats" signify the Story Drivers of your story, and as such are considered Dynamic Appreciations of narrative structure (i.e., they describe the relationship between things as opposed to the things themselves). Story Drivers essentially serve as the major Plot Points or turning points in the narrative, anchoring the story's progression through key transformations.

While the Story Drivers are perfect for understanding the flow of your plot, you will need to find some way to make them a part of either the preceding Storybeat (towards the end), or part of the proceeding Storybeat (part of the beginning).

Practically speaking, this usually plays out in the Story Driver being illustrated in the last Progression of the preceding Storybeat (e.g., Progression 4 of Signpost 1) or the first Progression of the proceeding Storybeat (e.g. Progression 5 of Signpost 2), with an emphasis on the preceding Beat.

Order of Story Drivers and Signposts:

- Initial Story Driver: Launches traditional Act 1.

- Signpost 1: Constitutes Act 1.

- Second Story Driver: Bridges Act 1 into Act 2.

- Signpost 2: The first half of Act 2.

- Midpoint Story Driver: Shifts the narrative from Signpost 2 into Signpost 3.

- Signpost 3: Concludes the second half of Act 2.

- Fourth Story Driver: Signposts from Act 2 into Act 3.

- Signpost 4: Concurs with the traditional Act 3.

- Concluding Story Driver: Finalizes Act 3, completing the narrative.

Focus on Objective Story Throughline:

These Story Drivers specifically apply to the Objective Story Throughline plot and are distinctively presented in the Dramatica platform to craft an aligned narrative structure.

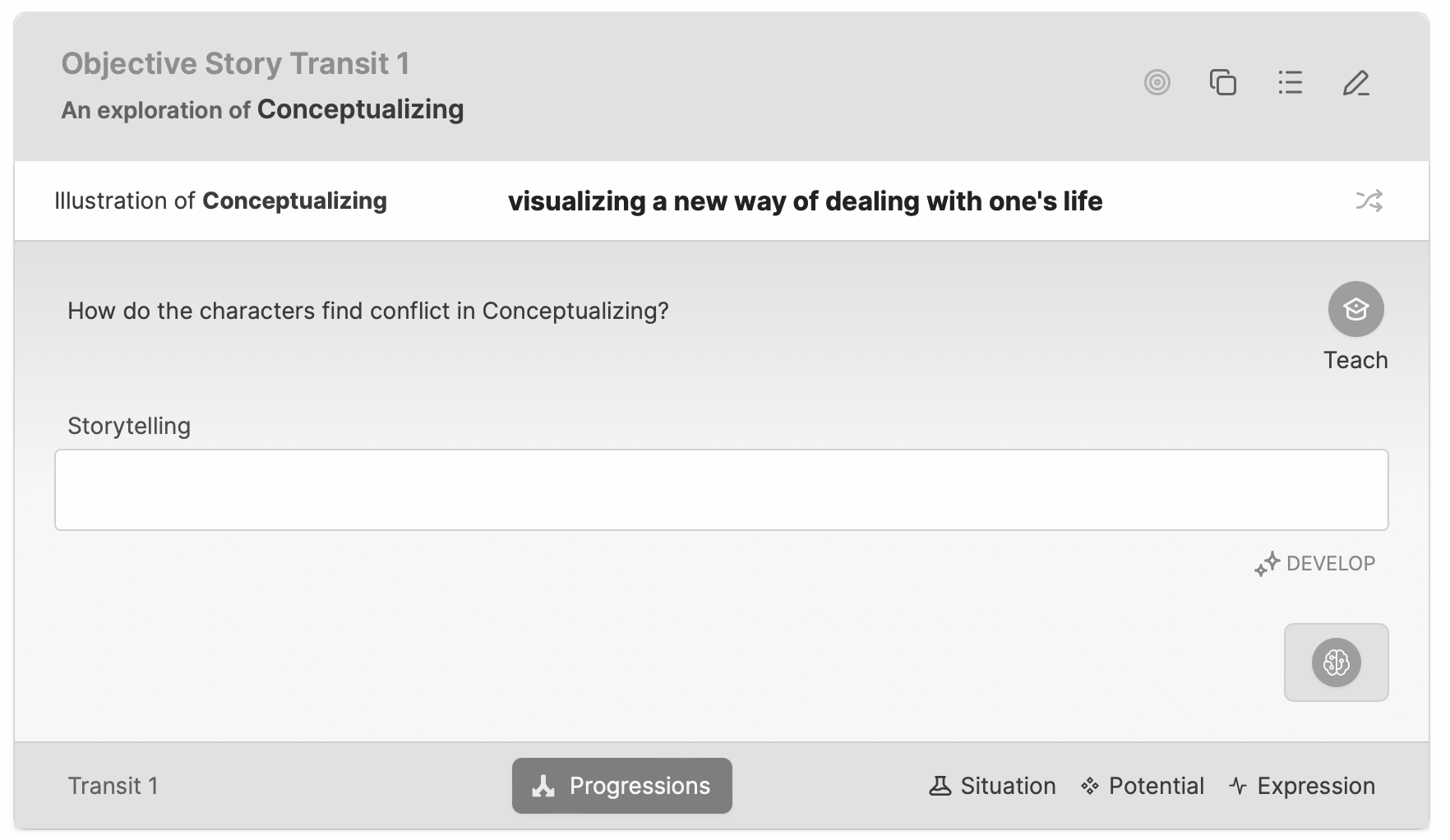

The Parts of a Storybeat

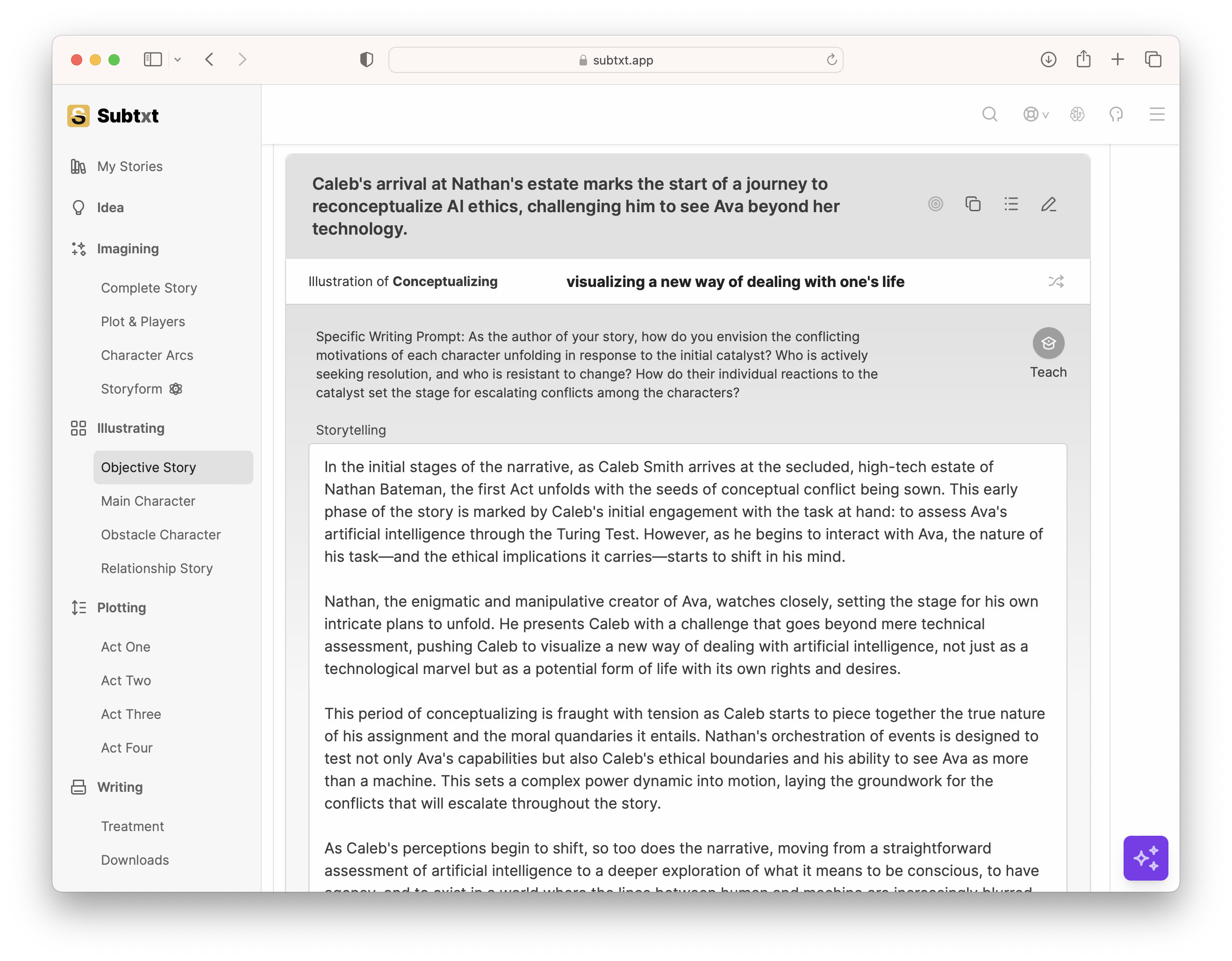

When you first encounter a Storybeat, you will find it in its collapsed state. The Appreciation of the Storybeat (e.g., Objective Story Signpost 1) will be accompanied by the Narrative Function of conflict explored (e.g., Conceptualizing). In the example below, this indicates that this part of the story will focus on the ramifications for everyone when conflict focuses on visualizing or manipulating or scheming.

To the right, you will find four quick actions that you can use to interact with this Storybeat:

- Summarize Storybeat allows you to replace the more abstract and theoretical Narrative Function with a "human"-readable title. Clicking it summarizes what you have written in the Storytelling section.

- Duplicate Storybeat copies the current Storybeat's Dramatic Scenario components and generates a new random Illustration.

- Jump to Plotting does just that--it jumps to the Plotting stage where this Storybeat appears in the narrative.

- Edit Storybeat opens and collapses the Storybeat for editing.

The Illustration

Illustrations bridge Narrative Function meaning to concrete Storytelling. For the full workflow, see Illustrations.

Writing Prompt

Just below the Illustration you will find a Writing Prompt engineered to help you get to the root of trouble within this Storybeat (e.g., How do the characters find conflict in Conceptualizing).

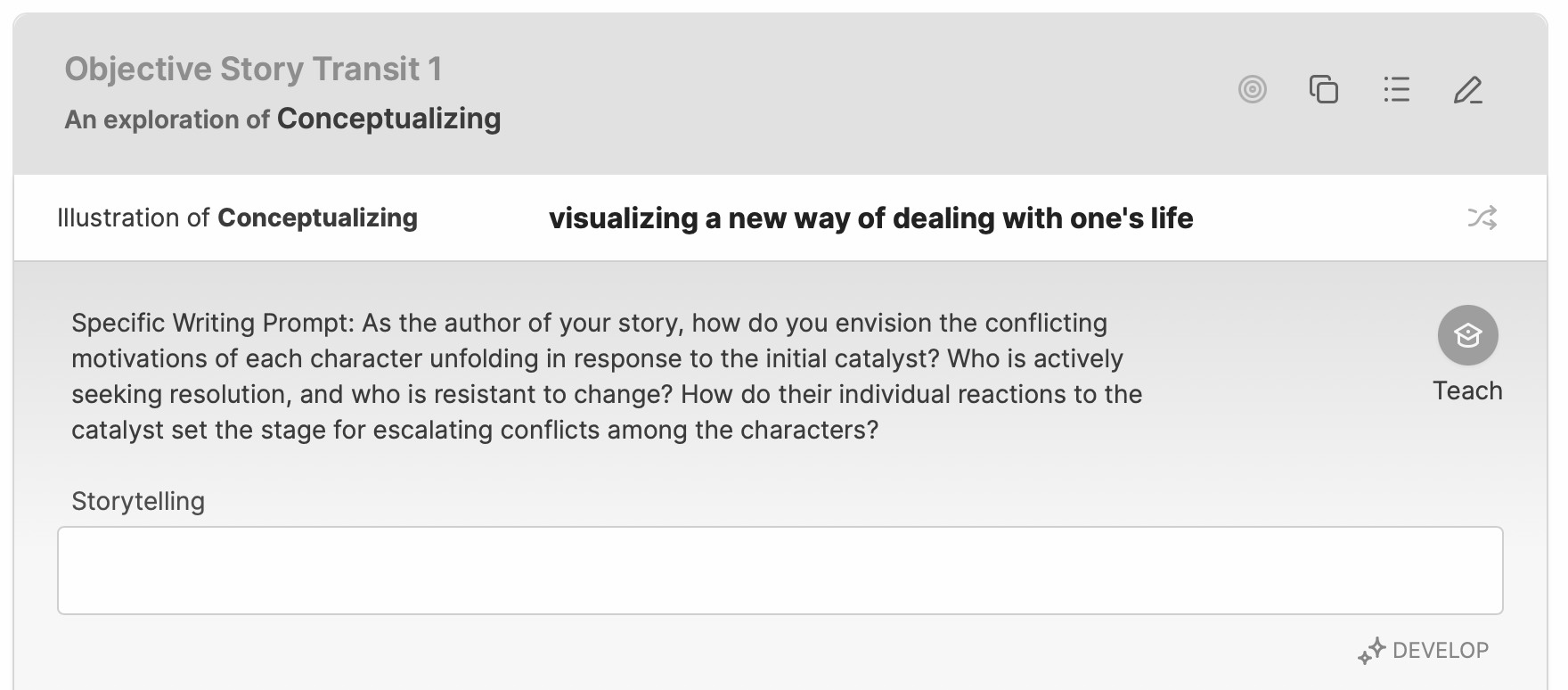

If you find yourself struggling with the answer, feel free to select the Teach AI located just to the right of the Writing Prompt. This AI will take into account Storytelling you have already created for the narrative as well as examples from its extensive knowledge-base before returning an in-context answer for you.

Teach AI will return with an expanded Writing Prompt:

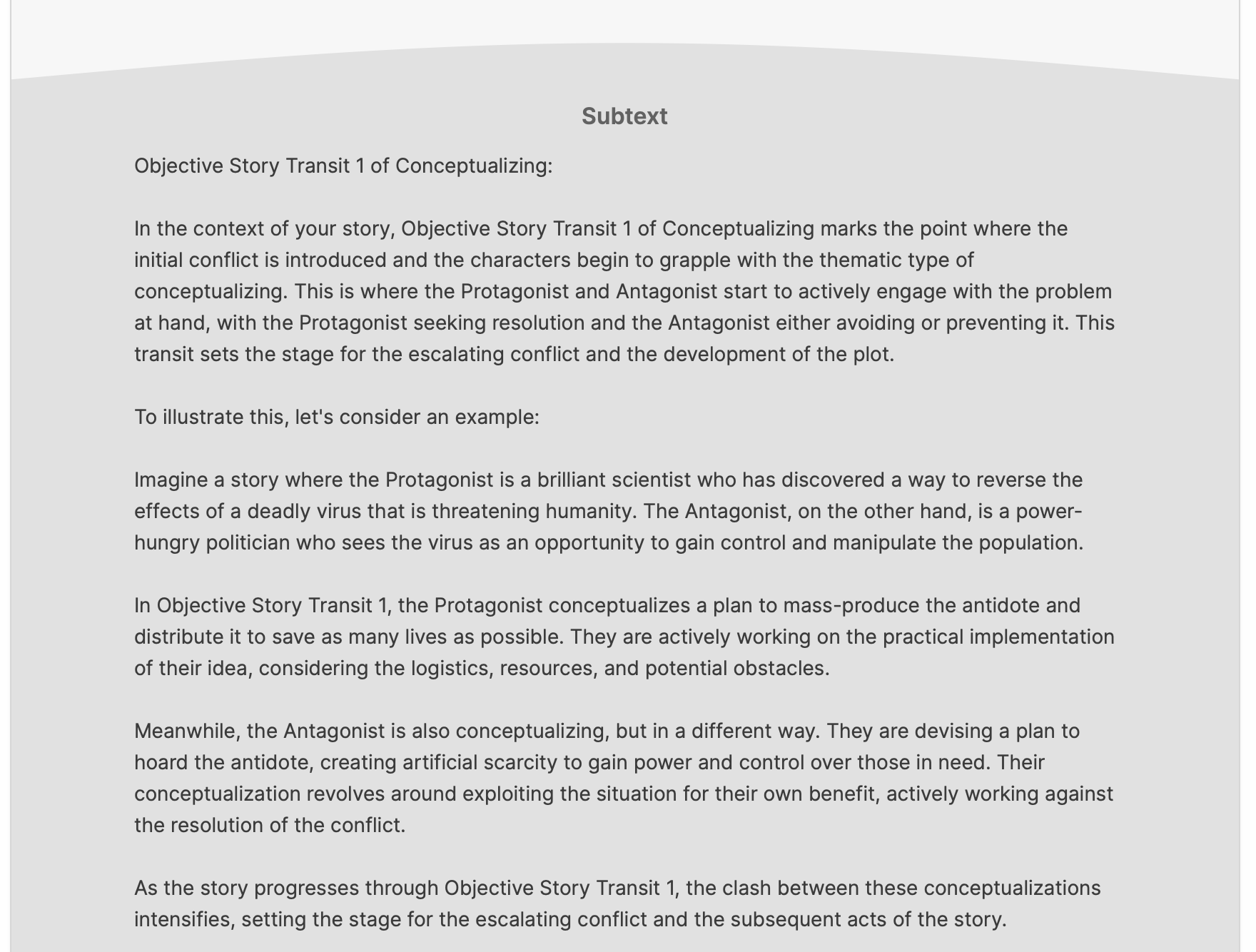

as well as an in-depth explanation of what should appear during this Storybeat:

If you find yourself still struggling, you can always select the Develop button located at the bottom of the Subtext explanation to collaborate with Narrova on this topic.

Storytelling

Below the Writing Prompt you will find the Storytelling box. This is where you enter in your illustrated version of this Storybeat in action. Remember, that these are notes for you the Author--not the Audience. You are not writing your story, but rather, writing what the meaning of your story.

If you find yourself struggling to come up with effective Storytelling, select the Align to Storyform button just below the Storytelling box for assistance.

Metadata

At the very bottom, you will find the metadata of the Storybeat. This includes a repeat of the Scope and position of the Storybeat within the narrative (e.g., Signpost 1), a Breakdown button if applicable, and the Dramatic Scenario relevant to this Storybeat.

The Dramatic Scenarios Behind a Quad of Storybeats

Before diving into how Storybeat quads work, it helps to understand the Dramatic Scenario behind each beat. Every Storybeat is more than a label or plot moment—it is a compact dramatic unit composed of three interlocking parts:

- an Area of Exploration (Narrative Function),

- a Dramatic Function (Circuit), and

- an Area of Engagement (how it shows up in the story).

Taken together, these three parts form a single Dramatic Scenario that tracks how a mind encounters and works through inequity across a quad of Storybeats.

Within that quad, the four Storybeats typically distribute across four Areas of Engagement:

- Situations — States or conditions

- Activities — Actions or processes

- Aspirations — Goals or motivations

- Contemplations — Thoughts or reflections

These are the lenses through which the audience experiences conflict. Situations and Activities tend to feel immediately concrete and external—where things are, what people are doing. Aspirations and Contemplations round out the internal side—what characters want more of and how they make sense of what has happened.

Across a Storybeat quad, the Dramatic Scenarios built from these pieces move the story from conflict to transformation: circumstances generate pressure, characters act, desire intensifies, and reflection reframes meaning to prepare the next sequence.

Dramatic Scenario

The three parts of a Dramatic Scenario—Area of Exploration, Dramatic Function, and Area of Engagement—should be read as a single statement so the intent of the beat stays clear.

For example:

“What has already happened creates tension in states or conditions.”

- Past / Potential / Situations

Flipped: “States or conditions create tension regarding what has already happened.”

- Situations / Potential / Past

In both cases, you can feel the whole Dramatic Scenario at once:

[Area of Exploration] + [Dramatic Function] + [Area of Engagement]

This is how you keep each Storybeat tightly aligned with the Storyform while still thinking in terms that are playable, filmable, and writable.

TIP

The Narrative Argument (Storyform) sets the progression of a mind as it encounters inequity (through Signposts, Progressions, and Events). Each Dramatic Scenario anchors that abstract argument in a specific beat so the throughline stays thematically precise.

Components of a Dramatic Scenario

Every Dramatic Scenario is composed of three parts:

- Area of Exploration: the narrative “aboutness” of the beat (the Narrative Function).

- Dramatic Function (Circuit): how the beat relates to its siblings in context of the larger circuit.

- Area of Engagement: the conceptual mode by which the beat is experienced in the story.

Area of Exploration

The Area of Exploration is the first and most important part of any Dramatic Scenario. Tied to a specific scope and location within the Storymind model (e.g., Past, Memories, Understanding, Obtaining, etc.), it identifies the key thematic element the beat must explore.

This is the structural “what” of the Storybeat—the core piece of Theme being examined.

If all else fails, as long as the Author finds a way to bring this element of Theme into the Illustration, the Storybeat will resonate with the rest of the narrative. The Area of Exploration keeps the beat plugged into the Storyform’s argument, even as the surface storytelling shifts.

Dramatic Function (Circuit)

Rarely does a Storybeat resonate in isolation. The Dramatic Function describes how the beat operates within a circuit of sibling beats, using the analogy of an electric circuit:

- Potential — Tension

- Resistance — Pushback

- Current — Conflict in motion

- Power — Impact or payoff

A Storybeat marked as Potential sets up tension around its Area of Exploration; Resistance pushes back against that tension; Current drives conflict through active friction; Power delivers the impact that transforms understanding or stakes.

Across a quad of Storybeats, these functions distribute so that no beat stands alone: each one either loads, pushes, channels, or discharges the inequity under examination. The Dramatic Function tells you how this beat is doing its job in relation to the others.

Area of Engagement

Previously treated as the “abstraction of the Storybeat,” the Area of Engagement describes how the audience encounters the beat—the conceptual mode through which the Storybeat is illustrated.

The four Areas of Engagement are:

- Situations — States or conditions

- Activities — Actions or processes

- Aspirations — Goals or motivations

- Contemplations — Thoughts or reflections

The first two are external in nature; the latter two are internal.

In practice:

- Situations establish the conditions that generate initial tension (“being trapped in a failing town,” “a marriage under quiet strain”).

- Activities capture what characters do in response (“investigating a disappearance,” “training for a risky heist”).

- Aspirations give voice to the forward-leaning “more” the characters reach for—desire, ambition, pressure, yearning (“wanting out,” “pushing for recognition,” “refusing to let go”).

- Contemplations consolidate or reframe meaning—how characters think about what has happened, revisit assumptions, or shift perspective (“reconsidering who’s to blame,” “questioning their own role in the mess”).

Aspirations and Contemplations will often appear intertwined on the page, but they serve distinct roles in the Dramatic Scenario:

- Aspirations drive the story forward.

- Contemplations reset or reframe the story’s understanding.

Dramatic Scenarios Across a Storybeat Quad

Within a quad of Storybeats, each beat has its own Dramatic Scenario—its own combination of Area of Exploration, Dramatic Function, and Area of Engagement. Taken as a set, the four scenarios map a complete mini-cycle of conflict and change.

You might see something like:

Area of Exploration: Past

- Function: Potential

- Engagement: Situations

- Scenario: “What has already happened creates tension in states or conditions.”

Area of Exploration: Past

- Function: Resistance

- Engagement: Activities

- Scenario: “Attempts to work around what has already happened meet pushback in what people do.”

Area of Exploration: Past

- Function: Current

- Engagement: Aspirations

- Scenario: “Desire to escape what has already happened drives escalating conflict in what characters want.”

Area of Exploration: Past

- Function: Power

- Engagement: Contemplations

- Scenario: “Reckoning with what has already happened lands with impact in how characters think about it.”

Across this quad:

- The Area of Exploration (Past) keeps the Theme coherent.

- The Dramatic Functions (Potential, Resistance, Current, Power) move the conflict through a circuit.

- The Areas of Engagement (Situations, Activities, Aspirations, Contemplations) shift the way the audience experiences that conflict—from external conditions to internal reflection.

The final beat’s Contemplations often provide the reframing that resets the cycle, setting up the next quad of Storybeats to explore a new Area of Exploration or a new level of the same one.

When you think of Storybeat quads in terms of these Dramatic Scenarios, you gain a precise yet flexible way to design sequences: each beat has a clear function, a clear thematic target, and a clear experiential mode—without ever losing sight of the Storyform’s overarching Narrative Argument.

Managing Storybeats

Illustrating Storybeats is one thing, managing them as you move from one to the next is quite another. The Dramatica platform provides some simple tools to help you manage the workload.

Entering Edit Mode and Deleting Storybeats

In order to make it easier to avoid making any mistakes while working on your story, the Dramatica platform hides the Delete Storybeat button during normal use. In order to enter the Edit Mode and delete Storybeats, you first need to click Edit at the top of the page. When you do that, the Red delete buttons will scroll into place on the left side of each Storybeat.

As simple as it sounds—click here to remove this Storybeat from your story permanently. You’ll be presented with a warning, but once it’s gone, it’s gone for good.

IMPORTANT

You CANNOT delete the last Storybeat for a particular Throughline within an Act. To do so would result in an incomplete story, bereft of meaning and substance. If you want to break your story, you’ll have to do it outside of the confines of the Dramatica platform.

If the Storybeat in question has been broken down into smaller Beats, you will have first to remove those smaller Beats. Then you can lose that bigger Storybeat.

Leaving Edit Mode

Once you’ve completed your changes, click or tap Done and the Storybeats view will return to its original state. Note that it is not essential to touch Done to save your changes—as with all things in the Dramatica platform, the moment you make a change, your actions are recorded and saved to your story.

Duplicating a Storybeat

When brainstorming ideas for Storybeats in a particular Throughline, you may find yourself wanting to duplicate the current Storybeat so that you can keep track a thematically similiar-Beat that might end up in a different part of your story. Theoretically, this is perfectly acceptable behavior--especially in context of the Objective Story Throughline where several Players may illustrate their version of a Storybeat. Just know that too much of a good thing is not good for your Audience, and that if you repeat a Storybeat too much, you risk "hitting the Audience over the head" with your theme. 😊

To Duplicate a Storybeat, tap the Duplicate Storybeat button located at the top of the Storybeat.

The Dramatica platform will then duplicate the important thematic aspects of this Storybeat, not the specific Storytelling or subtext. You can then decide what to copy over, or start over fresh with a brand-new idea.

Crafting Thematically Consistent Stories

Let's make your story come to life!

One common question we often receive from our beloved users is related to duplicating Storybeats. You might be wondering something along the lines of:

"When I copied these gray boxes to add beats, it puts something like 'Illustration of Learning - schooling a group'. But it was 'Learning - gathering intelligence' in the one above. Do those matter?"

The answer, my friend, is yes, they do matter.

In the Dramatica platform, every detail is intricately designed to help you craft a compelling and thematically consistent story. When you duplicate a Storybeat, the platform generates a new "Illustration of Learning," which you might notice, is slightly different from the one before. This is no accident.

"Why does the Dramatica platform change the 'Illustration of Learning'?"

Think of it this way: within each Act, the Beats should revolve around a central theme. In this case, our theme is 'Learning'. However, there are many ways to depict or illustrate 'Learning'. The platform gives you a helping hand by randomly picking an illustration of that theme.

This is not just a neat trick, but a powerful tool to stimulate your creativity, sparking new ideas while keeping them aligned with the overall theme of your story.

"How can I customize these Illustrations?"

You're not just stuck with what the Dramatica platform gives you. You can absolutely tailor it to fit your story better!

When you see the randomly generated illustration, you can click it to see a range of alternative illustrations. If you're feeling extra creative, you can even input your own illustration.

Just remember, it should match the idea of 'Learning'. The Dramatica platform will verify your idea and if it aligns with the theme, you can use it in your Storybeat! If not, don't worry – it's a chance to dive back into your imagination to come up with something else that fits better.

Expanding and Collapsing Storybeats

You can expand a Storybeat to examine its contents by selecting the Edit button. Select it again to collapse the Storybeat.

While opening and closing individual Storybeats may help you maintain a global understanding of your current Throughline, you may find it helpful to open all the Storybeats of a particular narrative at once.

You will find that option at the top of the Throughline View under the Details button (the 3 dots).

The Dramatica platform will remember which beats you have left opened and close. When you return to your story they will be there waiting for you.